Have you ever been to a city that gives off a subtle “message” of either resonance or dissonance?

Dissonance is sometimes easier to sense or feel. The first time I visited Sofia, Bulgaria, was in the winter of 2003, and I liked nothing about the city.

It was cold, gray, and ugly — trying unsuccessfully to shed its past communist rule. The buildings still bore the stark, utilitarian architecture of the Soviet era, their concrete facades chipped and weather-worn. The streets were lined with dilapidated infrastructure, strewn with potholes you could lose a car in, and the public spaces lacked vibrancy and warmth.

I couldn’t wait to leave the city. It was overwhelmingly depressing. The “message” Sofia sent me was subtle but unmistakable: a sense of dissonance.

Not all cities radiate a message. Most don’t. Most are mute.

In May 2008, Paul Graham, the co-founder of influential startup accelerator firm Y Combinator, published an essay, Cities and Ambition. (It’s an excellent read.)

I don’t recall when I first read it, but it left an indelible mark.

I reread it recently (a few times), and it’s provided me with language I didn’t have before in describing the “messages” some cities subtly broadcast to their inhabitants.

Paul Graham’s framing is mapped to the idea of ‘ambition.’ And I like that because it ties directly to why a particular collection of people are attracted to a city.

Because the message the city sends to these people is the same.

“Great cities attract ambitious people. You can sense it when you walk around one. In a hundred subtle ways, the city sends you a message: you could do more; you should try harder.”

“The surprising thing is how different these messages can be. New York tells you, above all: you should make more money. There are other messages too, of course. You should be hipper. You should be better looking. But the clearest message is that you should be richer.”

“When you ask what message a city sends, you sometimes get surprising answers. As much as they respect brains in Silicon Valley, the message the Valley sends is: you should be more powerful.”

“That’s not quite the same message New York sends. Power matters in New York too of course, but New York is pretty impressed by a billion dollars even if you merely inherited it. In Silicon Valley no one would care except a few real estate agents. What matters in Silicon Valley is how much effect you have on the world. The reason people there care about Larry and Sergey is not their wealth but the fact that they control Google, which affects practically everyone.”

Excerpts from Cities and Ambition by Paul Graham (2008)

When you talk about cities in this context, Paul Graham makes an interesting observation that what you’re really talking about is collections of people.

Cities implicitly “curate” a concentration of like-minded people.

As Paul Graham argues in the essay, Cambridge (Massachusetts) feels like a town whose primary industry is ideas, while New York’s is finance and Silicon Valley’s is startups. The message Paris sends now is: do things with style.

Cities provide an audience and a funnel for peers because it’s hard not to be influenced by the people around you climbing the same mountain.

Where opportunities not available elsewhere can take hold, and serendipity can thrive.

But when a city doesn’t send a message, it doesn’t attract (ambitious) people of a particular calling. And it’s discouraging when no one around you cares about the same things you do.

Sofia had that effect on me twenty years ago.

A city speaks to you mostly by accident — in things you see through windows, in conversations you overhear. It’s not something you have to seek out, but something you can’t turn off.

Bath in Somerset, UK, is one of those cities.

I can’t “turn off” the message I get from the city, a feeling that instantly resonated with me the first time I visited (and every time since).

I instantly fell in love.

I’ve since visited a handful of times, and each time the city sends me the same message: you should be an artist; a writer; a creative hell-raiser doing shit differently, a rebel, a misfit, one of the crazy ones.

The city seems to care for people like this, a subtle embrace, an insider’s nod invisible to everyone who doesn’t identify as a creative soul seeking a collection of their “weird” people.

… but, to me, the subtleties continue — the message from the old medieval city also says: you should love good food with local ingredients thoughtfully prepared and overvalue wonderful entertainment.

There’s a young vibe, too, thanks to the University of Bath (named University of the Year in 2023) contributing to the message.

I was there last month and had lunch with my dear friend and author, Joanna Penn.

I arrived a little early (I’m always early), so I popped into The Huntsman, a pub in stunning Georgian surroundings, and nursed an excellent locally brewed ale.

There was no desire to browse on my mobile. Not in this beautiful city, teaming with people. So I people-watched. Enjoying the atmosphere, the hum of conversations, random laughter, the clinking of glasses for celebrations unknown. The warm, rustic Georgian interior was filled with a mix of locals and tourists (two Spanish sat to my right), all contributing to the vibrant energy of the place. The aroma of hearty pub food wafted through the air, mingling with the hoppy scent of the ale in my hand.

I met Jo thirty minutes later at the OAK Restaurant, a two-minute walk just around the corner. She was already there, a white wine in front of her. She picked the spot, being the local, so I knew it would be wonderful.

But damn, was it “cozy” (aka small!) — no seats empty.

I’ve never tasted hummus, zhoug, and chickpeas like this before. Stunning! I’m so returning to this restaurant next time I visit Bath.

On the OAK website, it says:

As a grocer we specialise in organic, biodynamic and low intervention ingredients. At the heart of OAK is the idea that great food puts the soil first. As growers, grocers and cooks we want to sell produce and serve food that is simple and thoughtful, to find vegetables that not only look and taste great, but also come from land that has been farmed properly, without chemicals or over cultivation.

The city spoke to me over and over, like a faint signal in the air: you should be an artist, a writer, a creative hell-raiser. You should love good food with local ingredients thoughtfully prepared and overvalue wonderful entertainment.

Great cities attract ambitious people.

Walking around a great city, you can sense the ambition in the air. People are striving to achieve great things, and they are constantly surrounded by others who are doing the same.

People cut from the same weird cloth.

When surrounded by ambitious people working towards similar goals, staying motivated, focused, and energized can be easier, opening up opportunities not available elsewhere in such a concentration.

§

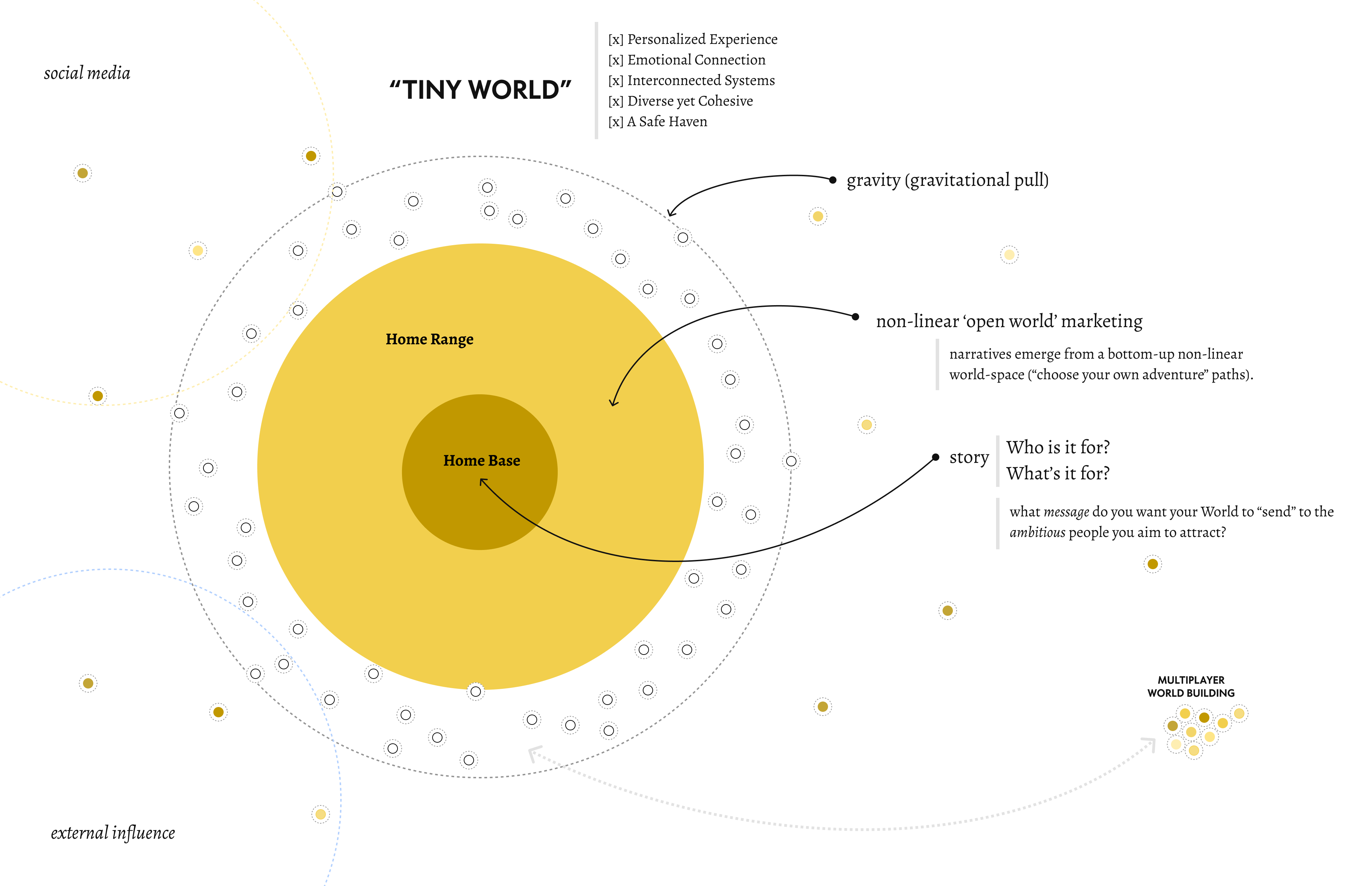

While Paul Graham’s essay focuses on (living in) physical cities, there is a noticeable analog to (some) online businesses.

As sovereign creators and Tiny World Builders, we architect non-linear Worlds for our audiences to inhabit, attracting ambitious people into our fold — the weird people we serve; the hell-raisers.

Like a great city, the “message” our Tiny Worlds says attracts a specific collection of ambitious people with common needs, wants, or aspirations.

For the sovereign creators I’m serving, the “city” I’m building here says:

- you can do better;

- the quality of your audience matters;

- delight the weird;

- the sacred act of earning trust and attention and fostering lasting relationships is worth the long-term effort;

- ‘open-world’ marketing is a container for this to happen, a canvas from which you build your Tiny Digital World.

This Tiny World I’m building for you to inhabit is still small but will expand over time — the “message” it sends you will become more distinct and clear.

I’ll leave you with a question: What ‘message’ do you want your “city” to send to the ambitious citizens you aim to attract?

Because make no mistake, like it or not, your website, your place of business — it’s putting out a message. Subtly, implicitly, or “by accident,” it’s there, talking to your people.

The message is an emergent property — a felt voice — from all the “parts” of your business interacting in ways that are not always obvious or predictable.

But it’s there. Talking. Attracting.

(And repelling.)

~ André