Ideas, much like fractals, reveal deeper complexity and variety the closer one examines them. This concept is not just a fancy metaphor; it’s a path to better writing. When we recognize that each idea contains multitudes, like the endlessly repeating patterns in a fractal, we unlock unlimited creative potential.

My friend Aiden Rayner shared some insights with me in an email the other day.

While Aiden’s email was about ‘how writing has become the superpower of his business,’ there is a broader insight, a meta-idea, that I want to draw attention to…

Good ideas, like insights, are fractal.

Think of a map. We zoom in for detail zoom out for context. Each level reveals something new, something we hadn’t seen before.

But here’s a thought: many of us rarely change our “zoom.” Too often, we find ourselves anchored to a single altitude of thought, one limiting perspective, missing the intricate patterns repeated at every level.

Let’s change that.

Let’s zoom in and out, exploring all angles.

We’ll start with Aiden’s email. It’s our anchor, our starting point to delve into the multilayered craft of writing.

Remember, this approach isn’t just about writing. It’s a universal tool for uncovering hidden depths in any idea and insight, revealing the rich layers hidden below — a path to improve any skill.

With Aiden’s permission, I’ve included his email below.

I hope you’re well, mate.

I just got to thinking about you. I ran into a quote from Conan O’Brien:

“It’s our failure to become our perceived ideal that ultimately defines us and makes us unique.”

Conan was talking about how he tried to be Letterman for much of his career, and always failed to do it. But the way he failed to be Letterman became what we know as Conan.

My writing, especially my emails, have become the superpower of my business. They’re making me stand out and get noticed. When I read that quote, like Conan with Letterman, I realized I’m trying to be you when I write. And it’s exactly my failure to achieve that which has become my unique voice.

It was a small moment, but a nice one. I wanted to share.

Thanks again for your part in my journey.

(Emphasis is mine, not Aiden’s.)

Good ideas are fractal.

Aiden’s reflection on his writing journey sows the seed for our deeper dive into the fractal nature of perspectives. As sovereign creators, writing is our shared canvas, yet it’s the individual strokes that define our voice and style. [efn_note]Arthur Schopenhauer, a 19th-century German philosopher, argues that an author’s style should be a reflection of his or her mind and vehicle of the thought process itself, which is what sets “classics” from inferior writing:

“A man who writes carelessly at once proves that he himself puts no great value on his own thoughts. For it is only by being convinced of the truth and importance of our thoughts that there arises in us the inspiration necessary for the inexhaustible patience to discover the clearest, finest, and most powerful expression for them; just as one puts holy relics or priceless works of art in silvern or golden receptacles. It was for this reason that the old writers — whose thoughts, expressed in their own words, have lasted for thousands of years and hence bear the honored title of classics — wrote with universal care.”

(Source: Schopenhauer on Style, The Marginalian)[/efn_note] [efn_note]Another thing that attracts me to private notes is how they talk at two levels. There is the content and then there is what Schopenhaur called the style, namely how a particular mind processed the content. All writing operates at both levels (and published works often deal with the content in a more systematic way, but the style comes through more strongly in private notes.

(Cited from On the pleasure of reading private notebooks, Henrik Karlsson, Escaping Flatland)[/efn_note]

Through his emails, Aiden has honed what he describes as the “superpower of his business,” a point of distinction in a vast sea of instructional chess content.

Aiden’s teachings unravel the game of chess, not merely as a battle of pieces on a board but as a dance of strategic conceptualization.

His insight, inspired by Conan O’Brien’s reflection on identity and failure, reveals a profound truth: It’s not in the emulation of our ideals where our voice is found, but in the space where we fall short and, in that shortfall, carve out our uniqueness.

Just as Conan found his signature in the divergence from Letterman, Aiden has embraced the pursuit of my style only to discover his own.

There’s a beauty in that.

Consider my friend Paul Wolfe, who, in the span of two years, has authored over twenty music books and just started writing about the intersection of self-publishing, writing, and the discipline of deliberate practice in his weekly newsletter, Practicing The Write Stuff.

Our primary mode of connecting with our audience is through writing, a medium that captures our unique voice, whether in digital text or transformed into spoken words in videos and podcasts.

And so, we circle back to the central question: How can we continue to evolve as writers, not merely to convey information but to construct a vibrant, living World for our audience to inhabit? (Herein lies the gateway to world-building.)

How do we hone our craft in becoming better writers and thinkers?

One way to improve our writing is to write more.

That goes without saying.

But it’s a partial truth. A single perspective among many.

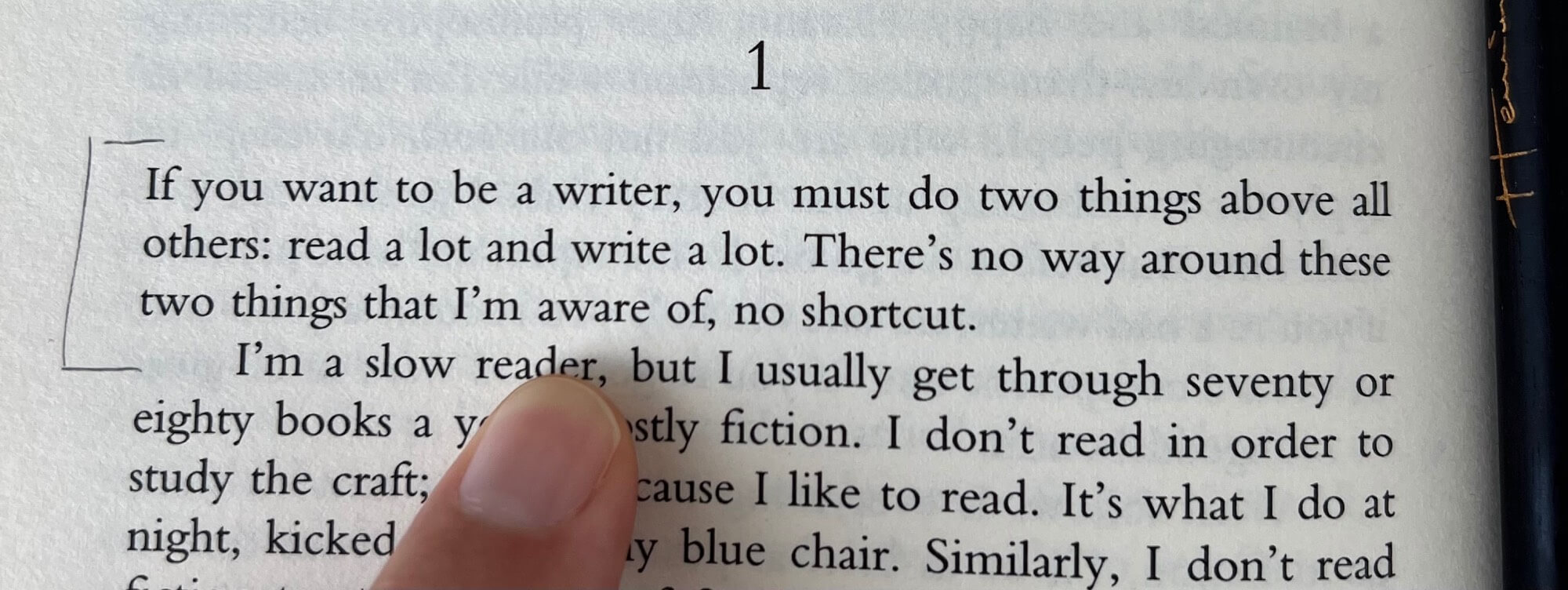

Stephen King’s wisdom in On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft points a way: read and write extensively.

So we need to read too. Which makes sense, of course.

But his, too, doesn’t tell the whole story. (A slightly more nuanced perspective zoomed in a little closer.)

Reading broadly is critical. And here’s where the plot thickens.

To improve as nonfiction writers, a common misconception is to read more nonfiction. You would think so, right?

But no.

Ellen Fishbein is a writing coach who works with people like David Perell (Write of Passage), Eren Bali (founding CEO of Udemy), and Shane Parrish (Farnam Street).

Ellen cautions against “Nonfiction Junkieism.”

Consuming nonfiction exclusively stunts a writer’s growth. She argues convincingly that fiction masters storytelling and wordsmithing — the very tools that elevate nonfiction.

A nonfiction junkie is someone who’s read a disproportionate amount of nonfiction versus fiction. Usually, it’s not that they don’t enjoy fiction, but it doesn’t feel useful or productive for them to read it.

They suffer the consequences when they try to become excellent at writing. Past a point, it’s hard for nonfiction junkies to improve as writers. They’re working with an unbalanced stash of resources from which to draw inspiration and solutions during the writing process — and some of the most powerful writing-related patterns & techniques are inaccessible to them, because fiction is the best teacher of those things. Even if they only want to write nonfiction, they still need the storytelling & wordsmithing skills that are most recognizable in fiction.

(Emphasis is mine.)

I can point to the moment I became better at nonfiction writing. It’s when I started to read fiction about fifteen years ago (I was thirty-five).

If you’ve been through any of my email courses, you’ll know I attribute the start of my fiction reading journey to Persuader by Lee Child in 2008.

I was a late starter to reading fiction (one of my few regrets). Until then, I had not read fiction, not since school.

The first sentence of Persuader crashed into me…

The cop climbed out of his car exactly four minutes before he got shot.

Huh?

I had to read that sentence again, … then again, until the implication dawned on me. I continued, the second sentence sucking me further in.

He moved like he knew his fate in advance. He pushed the door against the resistance of a stiff hinge and swiveled slowly on the worn vinyl seat and planted both feet flat on the road.

And just like that, I was hooked.

That first sentence is an example of an implied open loop (a powerful writing device in narrative fiction).

“… some of the most powerful writing-related patterns & techniques are inaccessible to them, because fiction is the best teacher of those things.”

So, my suggestion to you is to dive into fiction.

Read a lot of it.

And read cross-genres, another layer of perspective that may not always be obvious.

Your writing will sharpen more than any writing manual could promise. Guaranteed, or your money back.

Now, let’s get even more granular. Street-level granular.

Consider writing fiction. (For fun.)

I get it. Most people won’t do this.

It’s difficult. And it’s ego-destroying when we’re beyond terrible at the start.

But I’m not suggesting you write fiction to publish fiction.

You write fiction because the process is transformative. Active writing bridges the chasm from passive reading. It’s like a magic trick.

My forays into writing (bad) fiction are a (frustrating) work in progress.

Stories (and unfinished fragments of stories) that’ll never see the light of day. Which is fine. Because the act of writing fiction is the point.

It narrows focus. A convergence of story craft, where we’re forced to see things that are invisible to the passive reader.

(For more, see my essay in section 4 on Why I Write, which includes a short story of mine.)

The fractal nature of writing allows infinite zoom.

If we really want to push the limits of zooming right into the macro perspective, the extreme close-up, write the “first draft” of your fiction story as a screenplay.

Sounds odd, but it’s not.

This is my latest endeavor…

Bad screenplays join the bad stories. But ‘bad’ is beside the point. Or rather, bad is the point.

It’s about exposure to unseen patterns and techniques inaccessible to the internet’s nonfiction sprawl of mediocre writing.

Now, let’s pull back.

From this high 10,000-foot view, with fresh eyes, we craft our Worlds. Not just any, but magnetic ones, irresistible to those we seek to serve.

Aiden’s realization echoes here: striving to emulate a style; it’s in the shortfall where our unique voice finds breath.

From this broad, wide-angle perspective, our “expression” of the World we want to build for our audience can take flight unbounded.

I own my nonfiction voice. (I’ve written millions of words to find it.)

But my fiction’s voice? That’s under construction, shaped by the many authors I admire and seek to echo until my own voice and style emerge.

So, I persist in writing fiction in its various forms, badly at first. As I emulate my fiction heroes, my nonfiction skills sharpen almost as a natural consequence, an inevitable byproduct.

Neil Gaiman encapsulates this beautifully:

(from 20m40s) “… it’s absolutely possible that there are people out there who just have a unique voice. And when they write, they write in their unique voice and they get there. But I think for most of us, what we do is we start out sounding like other people. And we find our voice during the process of writing an awful lot. It’s a lovely line that I’ve been quoting for for decades now, which I was told, was said by Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead. Except that I’ve tried to Google to find the original, the only thing that I can ever find is me quoting — attributing it. So for all I know, I made it up.”

(…) “style is the stuff you get wrong. That if you were a perfect writer, if you were a perfect guitar player, it would be pristine, there would be nothing there — it would just be the sound of a guitar being played perfectly. But it’s the stuff you’re kind of getting a bit wrong that actually gives you the style. And that’s what people actually responding to. And again, I think you only get there by writing 100,000 words … writing 500,000 words … writing a million words. Pretty soon, you’re gonna sound like you.”

Source: Scriptnotes (616): The One with Neil Gaiman

This essay used writing to unravel the fractal nature of ideas, but this applies to all facets of our work as Tiny World Builders.

In time, your unique expression of world-building emerges, more you than the person or people you’re “trying to be” — something that is unmistakably ‘you.’

André