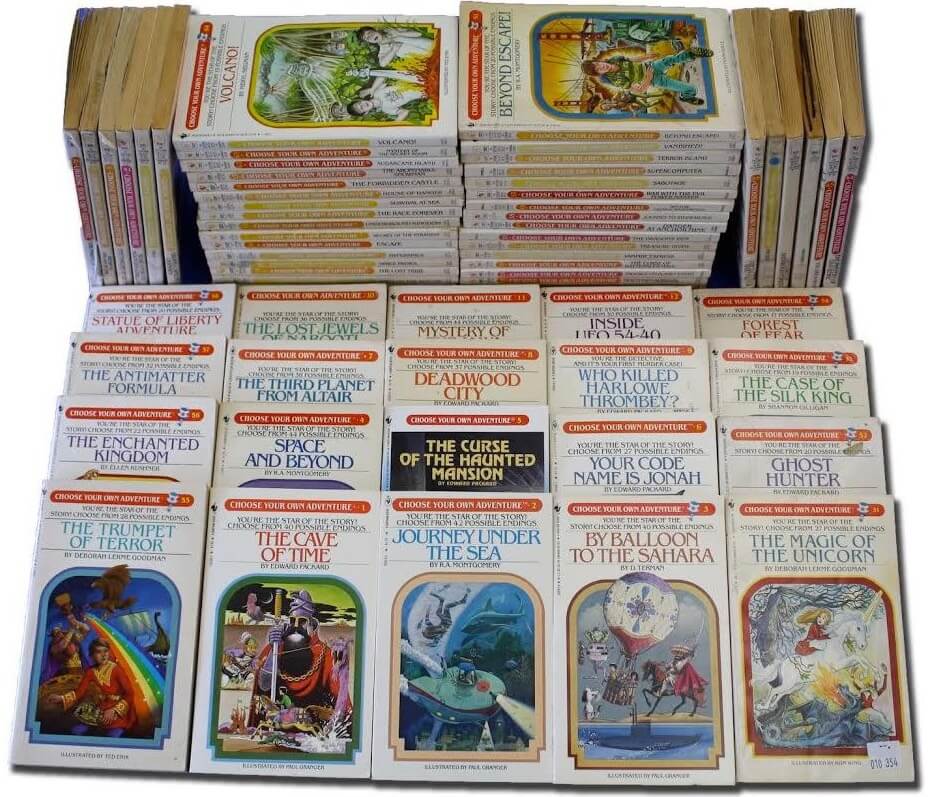

As a kid, I loved the Choose Your Own Adventure books, a series by Edward Packard (originally published by Raymond Almiran Montgomery) featuring stories written in the second-person perspective.

The second-person perspective is a point of view in storytelling, narration, or communication that primarily uses pronouns like “you” and “your” to address the reader directly (“Imagine you’re standing in front of a room full of people, about to give a speech. Your heart races, your palms sweat, and you feel a knot in your stomach…”). This perspective creates a more interactive and transformative experience, involving the reader in the narrative.

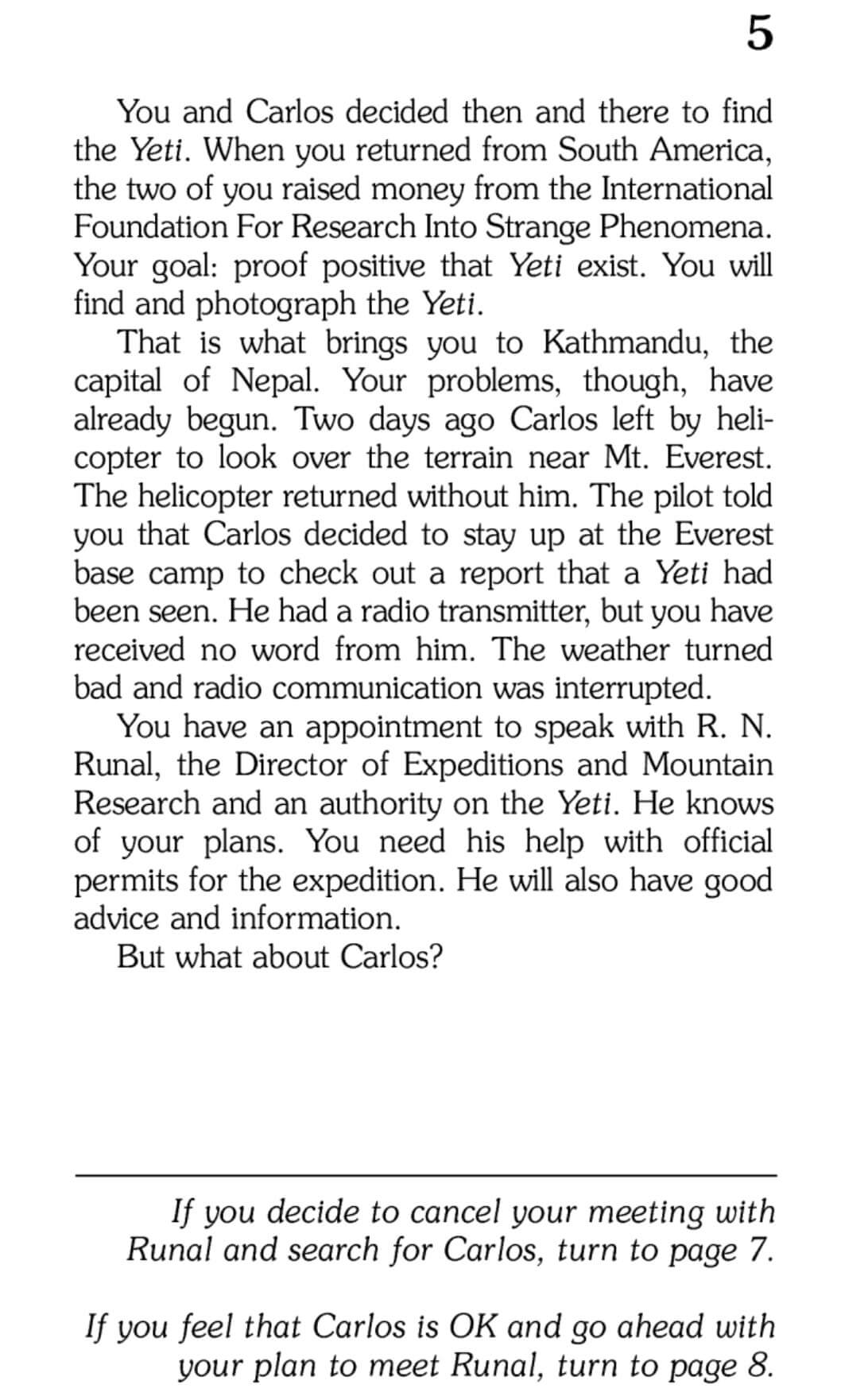

In these books, the reader takes on the role of the protagonist and makes decisions that influence the character’s actions and the story’s outcome.

Just think about how intoxicating that small but significant change in dynamic is for a reader. It shifts agency to them, inviting them to be part of the unfolding adventure.

These books (270 million copies sold!) created ‘worlds,’ each allowing the reader to “write their own story” by making nearly two dozen choices that could lead to around 42 possible endings.

These books appeared “to be as contagious as chicken pox,” said an article published in 1981. As I write this, What Should Danny Do?, published in 2017, has a rating on Amazon of 4.8 out of 5 (from 23,219 ratings).

This non-linear storytelling experience is the insight I want to draw your attention to, pointing to another way of imagining how we can create transformative customer-led experiences with our open-world marketing.

When you internalize this, how you think about marketing will change forever.

World Building

CYOA was an example of world-building, creating a more transformative experience through a non-linear narrative.

In fiction, film, television, and gaming, creators craft worlds for their stories and characters to move through, complete with geography, cultures, history, lore, societies, and rules.

You often see epic world-building in fantasy and science fiction, like The Silo, Lost, Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones, and the Harry Potter universe.

In 1999 Steven Spielberg hired scriptwriter Scott Frank and creative director Alex McDowell on the same day for a new film project: The Minority Report (released in 2002). The Minority Report is a 1956 science fiction novella by American writer Philip K. Dick. So while a world existed within a literary narrative…

No script had been written.

Spielberg wanted to do something different. He wanted to avoid this being a science fiction movie like the novella, but rather a future reality viewers could immediately relate to.

Alex McDowell got just a few “rules” from Spielberg (from a half-page synopsis):

- Location: Washington DC

- Year: 2054

- Disruption in the center: PreCogs

From this, Alex McDowell and his team were tasked with designing a world without a script.

The design of the world preceded the telling of the story. “The world became the container for narratives,” said Alex McDowell, “The world incepted the narrative in a fundamental way.”

The world McDowell and his team created became a container for narrative, and not just one narrative:

“We could have told hundreds of stories in this space,” said Alex McDowell. “We knew the world intimately. If Steven Spielberg had wanted Tom Cruise to turn left instead of right out of any doorway, we knew what was there. And it was clear that you could apply completely different lenses to the world developed for the film.

“Although our work supported a linear cinematic narrative, it could also have been used as a way of looking into the future of urban planning; targeted advertising; wearables; gesture-based interfaces; autonomous mobility, many diverse aspects of the world.”

“A kind of real-time, nonlinear process evolved throughout the production of this film, which tested not only how one might think differently about film production, but also how to think differently about developing a story. For the first time there were digital sets and design visualization allowing the director’s interaction with the film environment and digital characters long before shooting.

“What was also significant was that scenes emerged from the development of the world that would not have been in a script written in advance of production by a writer sitting in a bungalow in the Hollywood Hills and typing out 120 pages. The world had incepted the narrative in a really fundamental way. The fabric of the world had triggered the story.”

Alex McDowell: World Building (FoST), 2016 Future of StoryTelling Summit

(Fun fact: In a keynote speech at World Architecture Festival in Singapore, McDowell said that over 100 patents had been issued for ideas first floated in the movie the world-building grew beyond genre.)

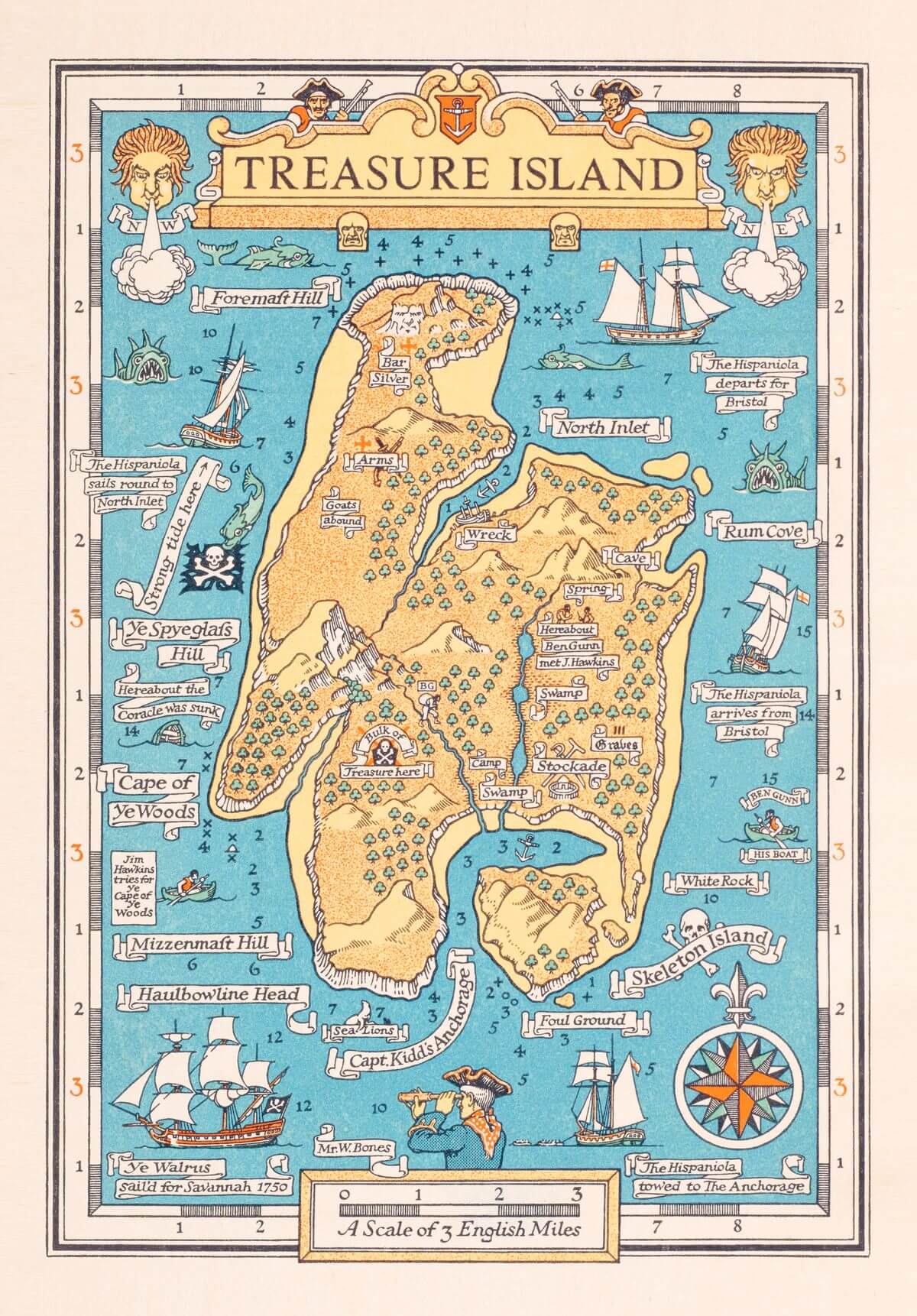

The principles of Tiny Digital Worlds draw inspiration from the concept of world-building found in great mythos-making, fantasy, and genre fiction.

As sovereign creators seeking a better, more open form of marketing, we craft a “Tiny World” that draws in the audience we seek to serve and have an impact on.

There isn’t a neatly illustrated Treasure Island “map” of our Tiny World. Instead, we employ content as a “narrative container” (including written, audio, video, images, and illustrations) to draw people forward in unique “Choose Your Own Adventure” (CYOA) style non-linear paths within an “open world” tailored to their curiosity and needs as they seek orientation, answers, and self-improvement.

This “map” doesn’t nicely adhere to the over-engineered linear path like the traditional sales funnel with its constant drumbeat of urgency ensuring people don’t “get lost” along the way.

Rather, the principles of world-building gently guide individuals towards areas of the world that can serve their needs at the right moment, earning their attention instead of demanding it.

The counterintuitive thing about Tiny Digital Worlds is you can get lost.

But losing yourself in a world is an essential aspect of embarking on a journey that transforms in magical and emergent ways that can’t be entirely engineered.

Extending the metaphor, the “treasure” hidden within our Treasure Islands is what our audiences are seeking — whatever that is within the context of your business and the needs you serve.

As previously stated, I believe that the best “marketing” in the world is marketing that’s mostly invisible to the person interacting with it.

Or said another way: the “tools” of marketing are invisible, and being pulled forward is felt, not seen. Where you self-identify as being a customer before any money changes hands. When becoming a customer feels like an inevitability and then it is.

Whether you’re:

- a business coach (like Art of Accomplishment or Martha Beck),

- a SaaS business (like Fathom Analytics or Basecamp or ConvertKit),

- an ecommerce store (like FOND Bone Broth or Blackwing or Crucible Tool by Lost Art Press),

- a writer (like Robin Slone or James Clear or Hugh Howey or Joanna Penn or Johnny B. Truant),

- an artist (like Charlie Mackesy or Grovemade or Van Neistat — see: Why Do Details Matter?),

- a book publisher supporting weird and experimental authors (like MCD Books or Altamira Studio or Holloway),

- a weird knowledge worker (like Daniel Scrivner, David Perell, Farnam Street by Shane Parish, Interintellect, or yours truly, of course),

- an agency (like Animalz or Breathe),

- an investment/business partner (like Tiny or Syrus),

- a health and longevity MD (like Peter Attia),

- a YouTuber (like Colin and Samir or Mark Lewis or Yes Theory),

- a slow newsroom (like Tortoise),

- a craft enthusiast (like James Hoffmann or Epic Gardening or Lost Art Press by Christopher Schwarz)…

… or a technology art studio like Hundred Rabbits, sailing the world supported by the work they create for their (true) fans.

Source: We are Hundred Rabbits (YouTube channel)

The concept of world-building for sovereign creators has a powerful effect on pulling in an audience, even when the specific elements that contribute to this are not always obvious from the outside.

Even after browsing the links above, it can be difficult to identify specific elements, as some are “hidden” while others are emergent and difficult to observe, but like a gravitational force operating through some complex non-linear alchemy, the “pull” can be felt by the people seeking the experience these worlds provide.

(In future writing, I’ll be taking some of the websites cited above — and others — and explicitly point to the elements that I feel contribute to their “Tiny Digital Worlds” experience to the degree I can looking in as an observer.)