This is a two-part series.

Note #1: I’ll be using the terms writers/publishers/creators interchangeably within the context of this essay. In doing so, I’m addressing all independent individuals with skills, ideas, and opinions so valuable that an audience is willing to pay for them. Whichever term you self-identify with, know I’m talking to you.

Note #2: If you’ve been following the recent “soap opera” between Matt Mullenweg (the founder/CEO/owner of WordPress/Automattic) and WP Engine, the billion-dollar hosting company, I want to clarify that I don’t have a position on it one way or another. As a sovereign creator, my only concern is using WordPress as my platform of choice. Regardless of the politics of how this legal battle between WordPress (Matt Mullenweg) and WP Engine plays out, WordPress as a platform isn’t going anywhere — and, pragmatically, that’s all I care about. After all, it powers almost half of all websites on the Internet (including mega-brands like Meta, TIME, Salesforce, Slack, Sony, TechCrunch, Playstation, CNN, WIRED, The New York Times, Microsoft News, and The White House, to name a few of the biggies).

Note #3: This essay began with a simple premise: expose the overlooked drawbacks and implications of Substack and present a superior alternative in almost every way — a self-hosted WordPress setup that offers better functionality (and “sovereignty”) at a fraction of the cost. As the draft expanded from 2,000 to 8,000 words, I decided to split the content into two essays. This first part focuses on the what and why of the Substack problem, while a follow-up essay will provide a detailed how-to guide for building your own self-hosted WordPress-powered alternative.

Introduction

We all need a piece of digital real estate to lay our digital foundations, build a presence an audience can find and engage with, and establish our online identity. Traditionally, this meant creating websites and blogs — our own self-hosted sovereign digital homes.

… but then, disruption happened. Shiny objects. Greener grass.

Social media platforms emerged, tempting many to build their presence on “rented land” rather than owning their digital property.

The social media platforms have (to great effect) enticed many creators and influences to cede sovereign in exchange for the promise of distribution, reach, and direct monetization (Facebook, YouTube, TikTok, et al.), negating the need for one’s own sovereign identity.

I get it. It’s super easy to create one’s presence on these social platforms. It’s free. What’s not to love, right?

While some creators “live” in both worlds — a brand website (WordPress, Wix, Squarespace, Webflow, Ghost) and on social media (X and IG and YT and TT), this two-worlds approach can get messy to manage and challenging/disorienting for an audience when there are different “homes” for a creator.

In the attention economy, it’s hard enough to capture and earn trust in one place, let alone have ourselves spread out wide, like glamping locations.

More recently (launched in 2017), Substack emerged as the latest disrupter in the publishing industry, offering yet another alternative that blends publishing, community, and monetization tools with the enticing promise of discoverability.

In 2019, Substack added support for podcasts and discussion threads. By late 2020, large numbers of journalists and reporters were flocking to the platform, driven in part by the long-term decline in traditional media.

In 2022, Substack added video to its platform. In April 2023, Substack implemented a Notes feature, which allowed users to publish and repost short-form content (competing with Twitter/X).

Since its inception in 2017, Substack has raised approximately $100.2 million through multiple funding rounds:

- Pre-Seed Round (January 2018): $120,000 from Y Combinator.

- Seed Round (April 2018): $2 million led by Fifty Years.

- Series A (July 2019): $15.3 million led by Andreessen Horowitz.

- Series B (March 2021): $65 million led by Andreessen Horowitz, with a pre-money valuation of $585 million.

- Equity Crowdfunding (May 2023): $7.8 million through Wefunder.

- Venture Round (November 2024): Approximately $10 million from strategic investors, including Omeed Malik, Nate Silver, Haroon Mokhtarzada, Mark Pincus, and Naval Ravikant.

These investments have supported Substack’s rapid growth as a platform for independent writers and content creators.

$100 million sounds wonderful.

However, what are the consequences of this?

That capital isn’t a gift — it comes with expectations. VC firms like Andreessen Horowitz don’t invest for fun; they aim for 10x+ returns.

Why this matters:

- Eventually, Substack must become highly profitable, likely through a mix of platform fees, upsells, ad-like models, or data-driven monetization.

- This creates tension between what’s best for Substack’s bottom line and what’s best for you as a writer/publisher.

- There’s a non-zero chance of “dark pattern” creep: nudges toward monetization, loss of editorial placement control, or algorithmic promotion driven by engagement metrics (not quality or values).

Think Medium’s journey from writer utopia to opaque paywalls and algorithm-led chaos.

Like any startup chasing growth and returns, Substack will evolve. As it does, it may drift from being a clean platform for writers into a closed ecosystem with behavior-shaping incentives.

The potential risk is loss of autonomy — Substack may begin steering reader behavior with:

- Suggested content outside your niche (this already happens)…

- Recommended newsletters that siphon away attention (this already happens)…

- Algorithmic rankings or feeds…

Or what if they change their fee structure? They already take 10% of paid subscriptions. What happens if they raise that? Or charge for essential features?

What’s more, because Substack is hosted and somewhat closed:

- You don’t own the reader experience or the platform skin…

- Your subscriber list is portable, yes — but not their behavior or experience…

- If Substack pivots to a model that doesn’t align with your values, your only recourse is to leave the platform — and risk losing momentum, trust, and revenue. (Switching cost is always a chaotic nightmare.)

This resembles the classic “platform risk” of building on YouTube, Twitter/X, or Medium — except it’s happening in the intimacy of email and paid subscriptions, where trust is paramount.

In the beginning, Substack’s customer is you, the writer. But over time, the gravitational pull can shift:

- From writers → readers (paying subscribers) → advertisers or

- data partners…

- And finally → investors who demand liquidity (IPO or acquisition).

Every step in this shift increases the likelihood that decisions will be made that don’t prioritize you as the creator. This is especially dangerous in subtle ways — Substack can say it’s creator-first while tweaking incentives behind the scenes.

Granted, most of these downsides haven’t happened (yet). But they could over time.

In Substack’s defense, they have resisted outside ads. They allow writers to retain full ownership of their subscriber lists. They’ve maintained a relatively clean interface (albeit a same-same look and feel for everyone).

If they continue to resist pressure, it could remain a valuable part of the ecosystem. But betting your whole “world” on that is risky.

Part 1 of this essay is to make a case for sovereignty — a piece of digital real estate you control.

“Build on platforms, don’t build within them” is my guiding long-term philosophy.

This approach offers the best of both worlds: we maintain our digital sovereignty by owning and controlling our online presence (“World”) while still leveraging the network effects of aggregation platforms like Substack, YouTube, X, Medium, and TikTok. This strategy ensures our content foundation remains secure even as we extend our reach across the digital landscape.

From a Tiny Digital Worlds perspective, you’re not just building a (paid) newsletter platform you own and control — you’re constructing a living, breathing World. You want:

- Infrastructure you control…

- Experiences you can craft…

- Freedom to evolve independently of third-party agendas…

With that out the way, let’s get started.

Why choose Substack?

When I’ve asked people using Substack why they chose it, a few primary reasons are cited.

Chief among these is the perception of ease. With Substack, the journey from thinking something to writing it, publishing it, monetizing it, and having readers reading it feels frictionless and straightforward.

The perceived “ease” of this workflow, without the need for any technical knowledge or hosting and membership/subscription considerations, has accounted for the stream of writers flocking to Substack over the past few years to plug into the gravy train.

However, “ease” is not always the best reason to choose one solution over another when other options offer more flexibility, greater control, and sovereignty.

I’m opinionated about sovereignty for creators who favor words as their primary method of communication. That said, I’m also referring to sovereignty more broadly — not just for creators who prefer words to oratory, but for all creators who publish content to serve an audience (where part of the sacred act of service is charging for some of that content).

“Sovereignty” is the primary theme of this piece. The case I’ll make is all framed through the lens of sovereignty. To respect your attention, I want to state this upfront — because if sovereignty is not something you value or care about, this essay and the follow-up one will likely not resonate with you.

While Substack can be a good fit for some creators (as my friend Paul notes, “If you write in any kind of niche where your writing is time-sensitive, then Substack’s model is great”), I would still argue that most of these creators would be better served by building their own self-hosted solution stack.

This approach eliminates any AI/algorithm or third party wedged between one’s communication and audience.

On August 25, 2024, my friend Paul wrote ‘Three Problems With The (Paid) Substack Model‘ on Substack, inspiring me to write this piece. (Yes, I know, it’s taken me a little while to complete this essay.)

⦿

There are incredibly successful writers on Substack: Letters from an American (2.3 million subscribers), The Pragmatic Engineer (975K subscribers), Lenny’s Newsletter (1 million subscribers), Slow Boring (202K subscribers), et al.

According to Press Gazette, these represent some of the highest-earning Substack newsletters. Edge cases.

This correlates with Paul’s earlier observation that Substack’s “perfect” audience is writers publishing “time-sensitive” information. Most of the highest-earners on the Press Gazette list write about news cycles, politics, and tech.

If you operate in these categories or another broadly popular “time-sensitive” category, perhaps Substack is the way to go. Maybe.

⦿

There’s another reason some creators who don’t fall into the “time-sensitive information” category choose Substack beyond the perceived draw of convenience and ease.

I suspect these creators also have a simple business model, which aligns perfectly with Substack’s value prop.

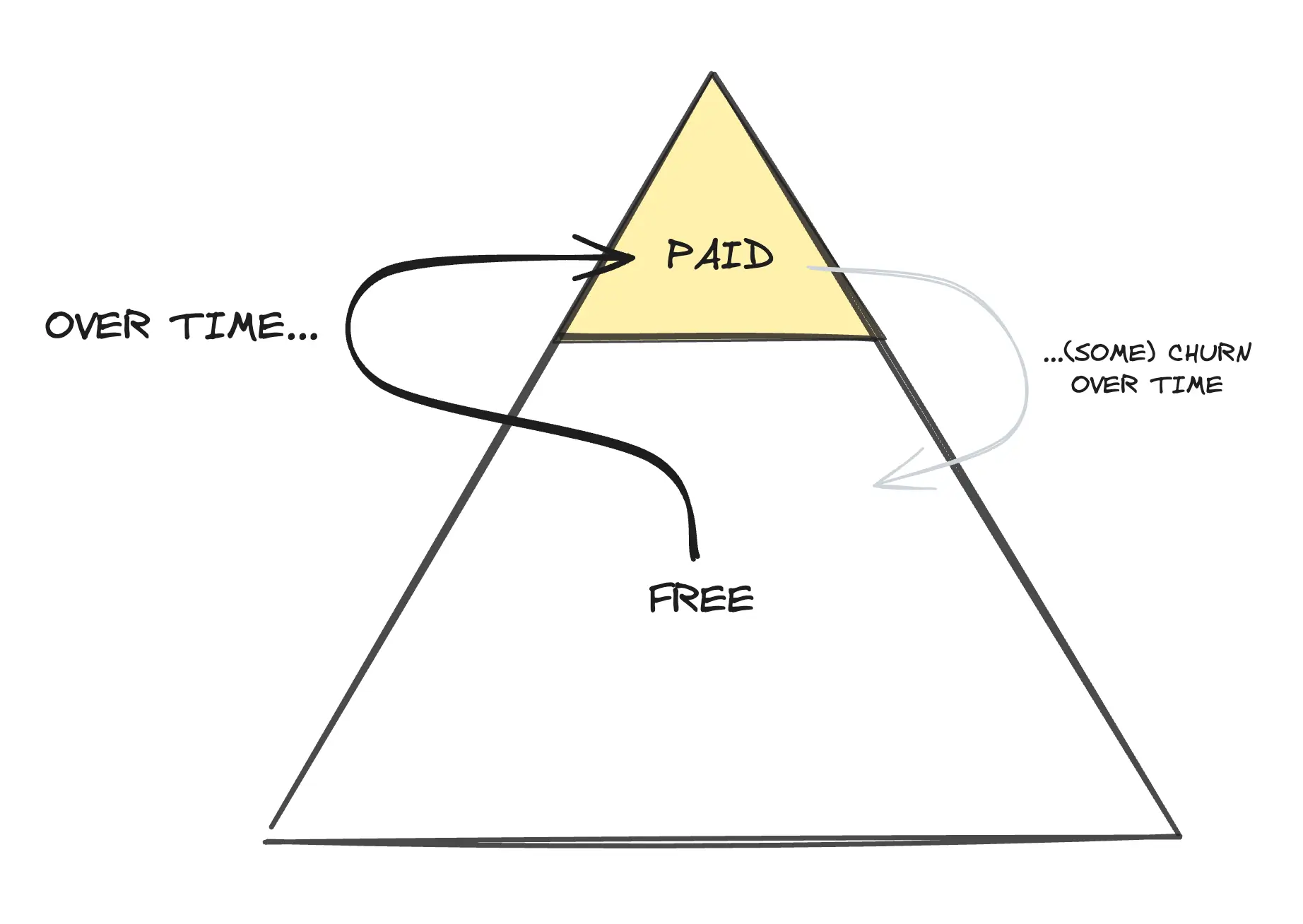

Most of their content is free, and some is paywalled. If you, as a subscriber, want a deeper level of commitment, you pay (either monthly or yearly).

George Saunders, a New York Times bestseller, Booker Prize winner, and creative writing professor at Syracuse University, offers a masterclass in storytelling and the craft of short fiction with a unique, educational Substack.

I joined (paid) when George launched his newsletter on Substack in 2021. I pay $50/yr. A monthly sub is $6/month. Since joining his community in 2021, it’s grown to more than 162,000 subscribers (27 Aug 2024) 296,000 subscribers (as of 26 Mar 2025)!

It’s reasonable to imagine that 5-10% of George’s subscribers are paid. That’s somewhere between $62K and $124K/month, which is not bad for a “sideline” newsletter in addition to his professional writing and teaching at Syracuse.

Chuck Palahniuk, the author of Fight Club, is another writer on Substack (40,000 subs).

However, it’s worth remembering that creators like George Saunders, Chuck Palahniuk, and others of their ilk are “celebrities” in their own right. They brought their significant personal brands with them to Substack.

For every Saunders and Palahniuk on Substack, a thousand unheard-of writers and creators are likely fighting an uphill battle to entice followers to their digital ghost towns.

Published on October 31, 2024, Newsletter Circle analyzed 75,000 Substack newsletters and found that 44% hadn’t published anything since April (a six-month window). Considering how easy it is to start a Substack, it’s not difficult to see that “easy” doesn’t translate into anything approximating success.

While I don’t doubt that George Saunders could create a far better customer experience on a self-hosted Substack-inspired newsletter platform on WordPress (more on this later and in Part 2), it probably doesn’t make sense for him.

Whales like Saunders likely choose Substack because they handle everything. Knowing that all the technical shenanigans are dealt with, he just has to show up, write, and teach. For that, Substack takes 10% (additionally, Stripe takes 2.9% + 30¢ per transaction). If he’s earning in the neighborhood of $100K/mo (splitting the difference I estimated earlier), Substack’s cut is $10K/mo, which is not insignificant. I suspect Saunders and others like him get the full white-glove concierge service.

⦿

There’s another powerful benefit I hear many people cite with Substack: the power of its “recommendation engine.”

All things being equal, Substack “promotes” its publishers through its recommendation engine.

I’ll demonstrate what this looks like.

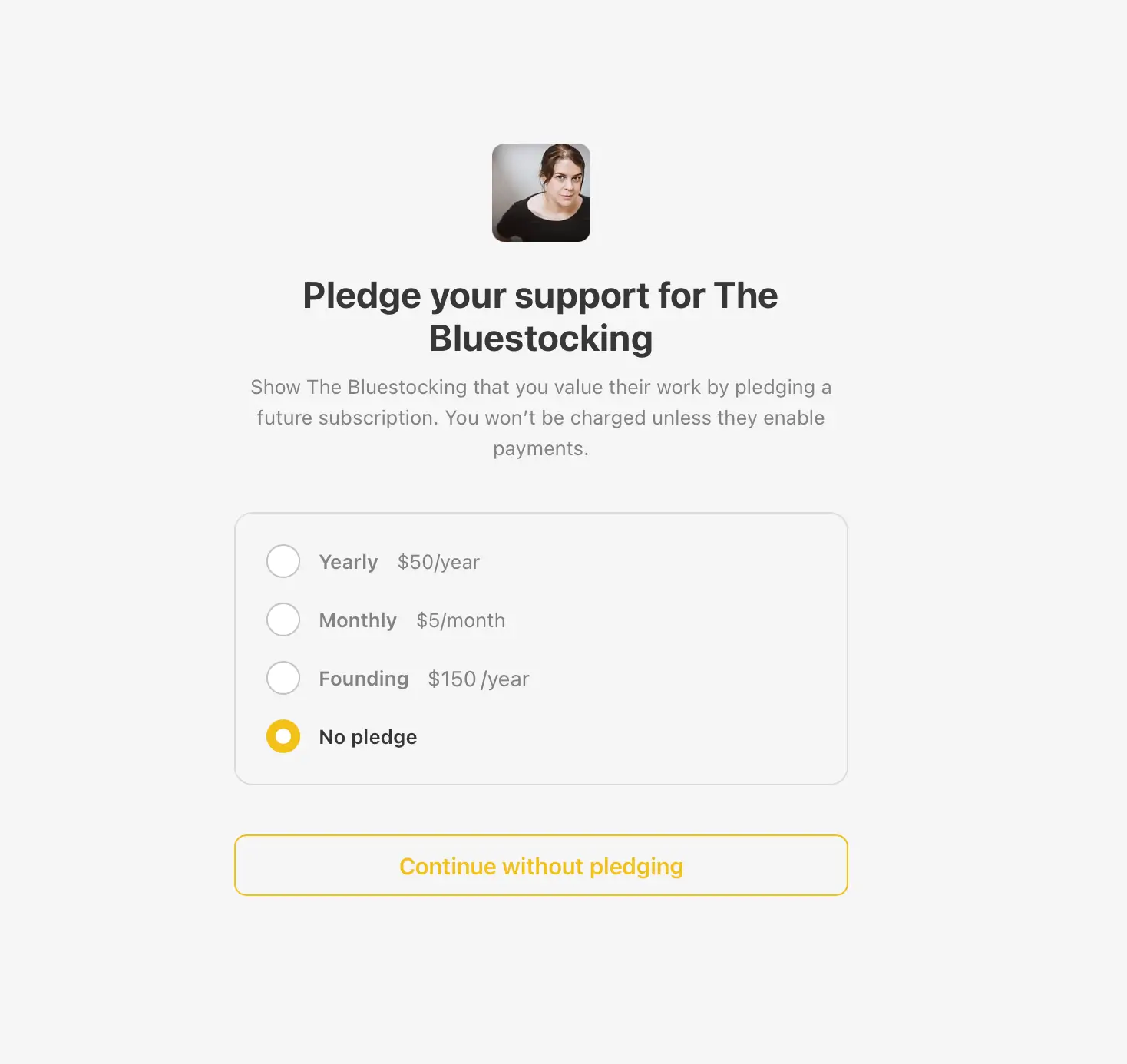

Here’s my attempt to subscribe to The Bluestocking by Helen Lewis. First, I’m faced with a decision to pay to support her work (nothing wrong with this). Yearly ($50/year) was selected by default, so I chose ‘No pledge.’

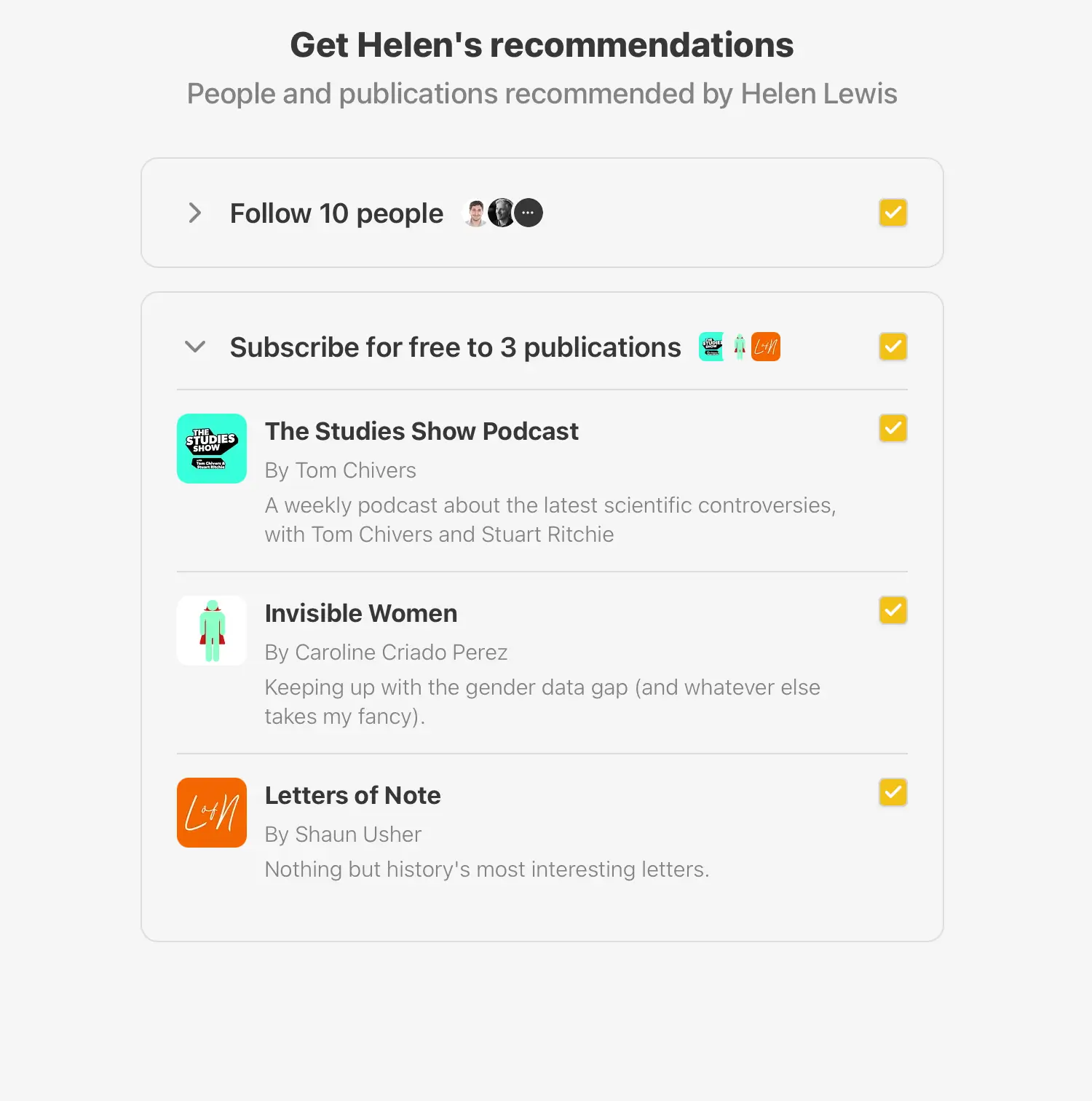

Now I get Helen’s recommendations, with ‘Follow 10 people’ auto-checked for my convenience, along with three additional publications, also auto-checked for my convenience (below).

This is where shit goes sideways for me…

I don’t know these 13 newsletter publishers, have no relationship with these authors, their perspectives, voices or narrative styles.

For thoroughness, I ran through this gauntlet with a different email address and faced different pairings — some the same, some different.

(What you can’t see on the screenshot above is that the ‘Continue’ button is pushed to the bottom of the screen, which is the default option). I suspect hitting enter on my keyboard would auto-subscribe me to all 13 newsletters (how convenient!). Not!

Clicking ‘Skip’ to continue with subscribing, I’m confronted with yet another option. The default selection, of course, is conveniently selected. I clicked, ‘Skip for now.’

The promotional gauntlet throws me one final attempt. Umm, thanks, but no thanks. I clicked ‘Maybe later >’

Phew!

I have a problem with this across a few dimensions, all fundamentally rooted around the concept of earned attention.

I’m already subscribed to many Substack newsletters (some free, some paid). Probably more than I have the attention bandwidth to read regularly.

Adding another 13 (in the example above), who I don’t know anything about, isn’t valuable to me. What’s more, I can’t even make a value judgment about whether they’re worth following, because there’s no link to each publication for me to make an informed assessment — it’s binary: opt-in (by default) or don’t.

Yes, Substack drives discovery, but I argue this benefit is, at best, misleading and, at worst, an entirely false benefit.

I’ve read about and spoken to several Substack writers who report a telling pattern in their stats: while they see bumps in free subscribers (yay!), these rarely translate into paid subscriptions (boo!).

If this pattern is representative across Substack, is their ‘recommendation engine’ truly worth the perceived benefit? This is, I know, one reason some people choose Substack over self-hosting — they believe it will ‘magically’ bring them exposure and subscribers through the network effect of the platform.

They just have to worry about writing. And their audience just shows up. Hmm…

Maybe not so much.

⦿

My (second) biggest problem with Substack, besides the lack of sophistication of their platform (their content publishing and email marketing is basic at best), is that you’re subject to their aggressive promotion of other Substacks (powered by their blunt-forced discovery engine as I’ve already demonstrated).

Join any Substack newsletter, and you’ll be pulled through a gauntlet of promotional opportunities to join other “related” Substacks, to pay right away (should you want), and finally, after batting away these attempts, complete your free subscription.

But wait, it gets better…

Substack sends out weekly digests (on by default, of course, but can be turned off — it’s a binary choice however; no nuance, no customization).

This is the one I received on August 26 (2024). Notice the subject line: Putin’s Legend and 5 more.

The third newsletter in the list, which I almost missed, is the one I cited earlier from my friend, Paul Wolfe. Besides the fact I nearly missed seeing it, his newsletter (about deliberate practice for writers) is associated, by proximity, with something about “Putin” (or worse still, Nazi newsletters). Fuck that!

You risk being associated with less-than-desirable newsletters on Substack, and there’s no way around this. They offer no controls to prevent this weirdness (short of opting-out of Substack’s recommendation digest and therefore, missing out on the exposure so many desire).

The reasons for this is partly because Substack technically doesn’t moderate content:

From the start, we have set out to encourage a broad range of expression on Substack. In most cases, we don’t think that censoring content is helpful, and in fact it often backfires. Heavy-handed censorship can draw more attention to content than it otherwise would have enjoyed, and at the same time it can give the content creators a martyr complex that they can trade off for future gain. We prefer a contest of ideas. — Chris, Hamish, and Jairaj (Substack founders)

However, while I broadly support their liberal view, the symptom of thousands of diverse writers publishing on the same platform across every imaginable topic often leads to weird and undesirable situations, as I demonstrated above (Paul and Putin in the same email digest).

This “feature” may not bother you, but it does me, and I know it does others. (If you’re seriously considering Substack, read the article cited below or listen to the podcast convo.)

Platformer’s Casey Newton on leaving Substack and surviving the great media collapse — The Verge

More recently, CJ Chilvers wrote this in his newsletter:

I tell newsletter newbies to start on Substack because the discovery on that platform is currently the best in the business. I started a secret newsletter there a while ago and got 99 subscribers in a few weeks without even trying. However, I also tell those newbies to get out of Substack as soon as they hit a plateau, because Substack does not have your long-term interests in mind. Last week, Anil Dash made that point (although I disagree with some of what he said) and John Gruber joined in with even better points. Gruber added, “My advice to any writer looking to start a new site based on the newsletter model would be to consider Substack last, not first…there are clearly better options, and the company’s long term goal is clearly platform lock-in.” I may have to re-think my recommendations to the newbies. — CJ Chilvers, 26 Nov, 2024 (Source)

Once again, it’s worth reading Anil Dash’s full perspective:

We constrain our imaginations when we subordinate our creations to names owned by fascist tycoons. Imagine the author of a book telling people to “read my Amazon”. A great director trying to promote their film by saying “click on my Max”. That’s how much they’ve pickled your brain when you refer to your own work and your own voice within the context of their walled garden. There is no such thing as “my Substack”, there is only your writing, and a forever fight against the world of pure enshittification.

… and John Gruber’s comments in full (excerpts below):

I am upset by the above, but only insofar as I’m jealous that I had never thought to make the analogy to an author telling people to “read my Amazon”. A publication on Substack is no more “a Substack” than a blog on WordPress is “a WordPress”. It’s really quite a nifty – but devious – trick that Substack has pulled to make this parlance a thing.

What I object to isn’t their laissez faire approach to who they allow to publish on their platform, but rather how they present all publications. People do call the publications on Substack “Substacks”. And Substack publications do all look the same, most of them right down to that telltale serif typeface, Spectral, 2 which is kerned so loosely it looks like teeth in need of orthodontia. It’s not an ugly font, per se, but it is very distinctive, which contributes, I think significantly, to the blurring of the branding line between Substack publications as discrete standalone independent entities or as mere sections under “Substack” as an umbrella publication.

Substack, very deliberately, has from the get-go tried to have it both ways. They say that publications on their platform are independent voices and brands. But they present them all as parts of Substack. They all look alike, and they all look like “Substack”. I really don’t get why any writer trying to establish themselves independently would farm out their own brand this way. It’s the illusion of independence.

Substack no longer even hosts a majority of the newsletter-style writers I subscribe to. Casey Newton moved Platformer from Substack to Ghost in January. Craig Calcaterra moved his excellent baseball-focused-but-with-heavy-dashes-of-politics-and-pop-culture Cup of Coffee from Substack to Beehiiv in January as well. Molly White runs Citation Needed on Ghost. My newest paid subscription is to CNN expat Oliver Darcy’s new media-industry focused Status, for which he chose Beehiiv. And of course there’s my friend and Dithering co-host Ben Thompson, whose Stratechery, running on his own platform Passport, not only long predates Substack but served as their model to replicate. (Substack’s pitch deck was “Stratechery in a box.”) All of these sites look distinctive, with their own brand. All of them offer much better subscription and delivery management interfaces than Substack.

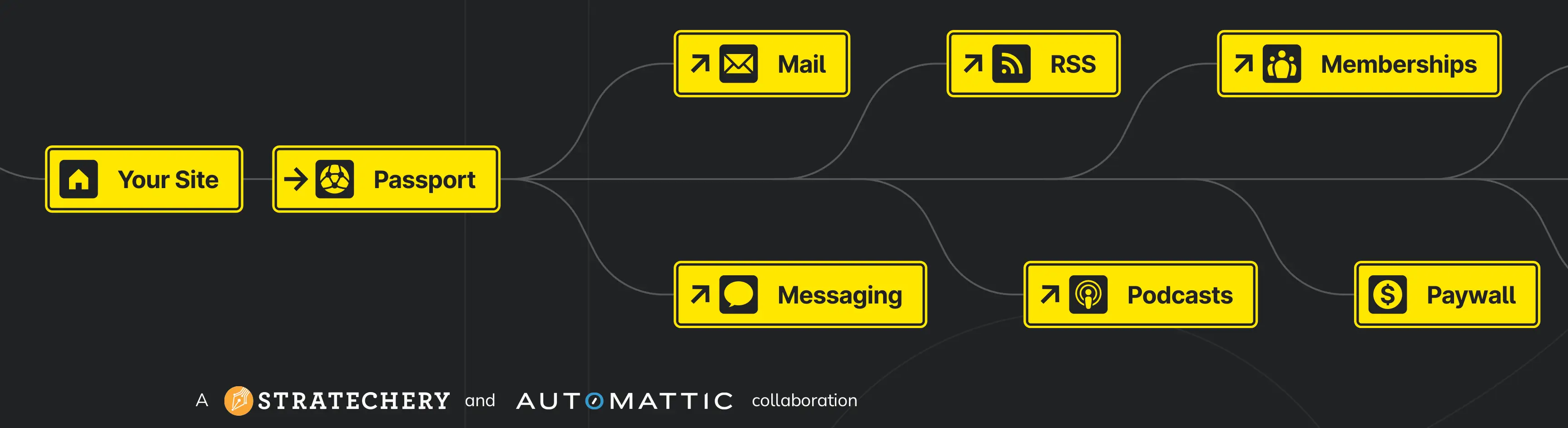

I’ve long admired Ben Thompson’s Stratechery, which predates Substack and Patreon. Ben built a one-person newsletter that generates about $3 million/year and became the envy of journalists.

Stratechery (and Dithering) are now powered by Passport, a subscription “platform” collaboration with Automattic (WordPress).

Stratechery started as a ducked-tapped tech stack of WordPress and Memberfulbefore Patreon acquired Memberful in 2018.

We guessed that perhaps the biggest reason more writers didn’t do what Ben was doing was just that it was hard. Ben had strapped together various tools, like WordPress, Mailchimp, and Memberful, to constitute Stratechery’s “stack” — we counted 19 tools in total — and it took a lot of work to make them play well together. (The age of the sovereign creator by Hamish McKenzie)

Passport is still WordPress.

It’s just a more elegant and integrated tech stack with WordPress (at the core), with integrated subscriptions, podcasts, and email.

While I’ve never used Passport (I’m on the waiting list), the tech stack I’ll describe later — which I use myself — is essentially an off-the-shelf version of it. Today’s integrations between different services are much more seamless than the duct-tape solutions of the past, thanks to elegant and inexpensive automation tools that connect through native integrations, APIs, and hooks.

Email Sophistication

There is no communication service on the Internet with a higher ROI than email, which is at the core of every successful business online and off.

However, the level of email sophistication offered by Substack is basic at best and nonexistent at worst.

This is my biggest issue with Substack-as-a-service.

The workflow goes like this:

You write your piece of content in the editor, then click publish. This does two things:

- It publishes the piece to your Substack subdomain (or proper domain if that’s been set up) as a new page…

- It broadcasts an email version to all your subscribers (free + paid, or you can choose one or the other).

Umm … that’s mostly it.

There’s no audience segmentation beyond free vs. paid.

There’s no welcome email sequence for new subscribers entering your world. Nothing.

(Substack offers a single welcome email for free and another for paid. Not a sequence, but a single email. That’s it. Like seriously.)

New people just enter a content stream (the next thing you send after they’ve subscribed), which can be a jarring experience.

When I started using email in 2003, I used AWeber. Even back then, automated follow-up sequences were the mainstay, the lifeblood, of email autoresponders.

It’s hard to believe that in 2025, a service like Substack with its $100 million in funding — where email is such an essential and personal component of communicating with one’s audience — doesn’t allow publishers to interact with new subscribers through a pre-written series of emails, introducing them to their new “world.”

Maybe Substack is the only service in the world that uses email as a core delivery vehicle and doesn’t offer follow-up sequences.

(Head scratching.)

Kit (formerly ConvertKit), the email-first “operating system” for creators I use, offers a decent free plan: one sequence and up to 10,000 subscribers. (Here’s a review of Kit.)

While one sequence is the bare minimum, two are a better minimum: one for a general welcome sequence and one for an “evergreen” newsletter. (The latter is beyond the scope of this essay.)

OK, so enough about the unbounded virtues of Substack…

Let’s explore how to build our own self-hosted Substack-inspired newsletter platform that you completely own and control.

… and that’s (almost) free outside of hosting (you save on the 10% rake Substack take).

However, I want to be quick to emphasize that the point isn’t whether this tech stack is free or not. Paying for various low-cost services is important because it ensures the long-term survival of these services/tools/plug-ins, and that matters (a lot!).

I’m arguing for sovereignty first and foremost. Achieving this far (far) less expensively than a 10% forever-fee is a welcome bonus.

Update (Feb 2026): I recently read a Substack piece by David I. Adeleke (Communiqué) — HT to Ryan C for the share — examining the evolving promise of platforms and the future of independent writing on Substack.

This recent move by Substack doesn’t surprise me. Sadly.

As David observes, what once felt like a writer-first sanctuary has been reshaped by growth narratives, capital incentives, and the expanding “creator economy” — with all the trade-offs that entails.

His analysis reinforces why I explored alternatives in this series: when infrastructure begins to define what writing should be, rather than support what writers choose to make, the craft risks being flattened into another growth vector.

The choices we make about where and how we publish matter — not just for reach or revenue — but for depth, trust, and long-form thinking.

I’ve said this before:

We’re sovereign creators because we choose independence. We build our own equity. We own our audience. We control our distribution.

“Sovereign” isn’t branding. It’s a posture.

It means we retain control and ownership of our work — with the freedom to determine how, when, where, and why it’s created, distributed, and monetized.

If you publish on Substack — or are considering it — David’s piece is worth your time:

https://www.readcommunique.com/p/substack-lost-its-way

~ André (18 Feb 2026)