It’s not easy to unsee or unlearn the type of traditional direct-response marketing that got us here.

There’s safety in taking the baton and continuing to do what our forebears started, now enhanced even better and faster and easier with technology.

What’s not to get excited about?

Why fuck with something that’s always worked and still works to the degree it does?

Because doing the “safe” thing is riskier than ever, as everyone with their AI-enhanced tools races to the bottom in a blur causing blindness to a new reality.

However, for a moment, forget about the hyperbole around AI and the merits associated with traditional direct-response, such as they are.

In many ways, we can get a sense of the answer when we look internally, not externally at what everyone else is doing.

As a prospect and customer yourself, what marketing do you hate being subject to?

And what marketing lights you up, where you enjoy the process of becoming a customer?

In my estimation, the best “marketing” in the world is marketing that’s mostly invisible to the person interacting with it. When becoming a customer feels like an inevitability and then it is.

No overt “free webinar” pitches, no over-engineered urgency, no fake scarcity, or any other signals of coercion that are impossible to miss.

I call this “Open World” marketing…

But to get there, we need to continue on this journey, like an onion, peeling away at (some of) the critical layers that contribute to an open-world experience.

What if the internet is like Tokyo?

Today there’s a market for everything, no matter how obscure or weird. Delighting the weirdos and outliers is the business model of the long tail.

Meet Kat Norton, a.k.a. Miss Excel, the spreadsheet queen who’s living the dream and proving that business can be a blast!

At just 29, she’s built a $2 million-a-year empire and crafted a lifestyle that’s both wildly profitable and more fun than should be legal.

And her secret sauce?

Using a framework of “fun” to teach spreadsheet tricks online. In November 2020, our girl Kat identified an opportunity to embrace her weirdness, entertaining her fans on TikTok while teaching something famously bland and boring.

She started selling an online course on Excel, and within two months, she was raking in more than her day job salary! Naturally, she waved goodbye to her 9-to-5 and dove headfirst into the thrilling world of content creation, but doing it uniquely differently to her peers and incumbents, on her terms, in her own unique and quirky way.

Since then, Miss Excel has launched nine more courses, covering other Microsoft programs and Google Sheets too.

By April 2021, she celebrated her first six-figure month, pocketing a cool $105,000. And just six months later, she made a jaw-dropping $100,000 in a single day.

Talk about turning fun into a fortune!

Derek Thompson, in a conversation with Barry Ritholtz for Masters in Business, externalized this dynamic using a fascinating metaphor: “The Internet is like Tokyo.”

…there is a paradox to scale, I think. People who want to be big sometimes think, “I have to immediately reach the largest possible audience.” But in a weird way, the best way to produce things that take off is to produce small things. To become a small expert. To become the best person on the internet at understanding the application of Medicaid to minority children, or something like that.

And the reason why I think this is true I call my Tokyo example. If you go to Tokyo, you’ll see there are all sorts of really, really strange shops. There’ll be a shop that’s only 1970’s vinyl and like, 1980’s whisky or something. And that doesn’t make any sense if it’s a shop in a Des Moines suburb, right? In a Des Moines suburb, to exist, you have to be Subway. You have to hit the mass-market immediately.

But in Tokyo, where there’s 30-40 million people within a train ride of a city, then your market is 40 million. And within that 40 million, sure, there’s a couple thousand people who love 1970’s music and 1980’s whisky. The Internet is Tokyo. The Internet allows you to be niche at scale.

Niche at scale is something that I think young people should aspire to.”

As the internet grew from one to hundreds, from hundreds to thousands, and now to well over a billion websites and over 5 billion people with wallets, many people didn’t see the “magic trick” happening right before their eyes.

It was easy (and still is!) to be suckered into believing that in order to succeed and capture audience attention, we had to seek to be a version of all things to all people.

But all things to all people is a losing strategy today. Just like doing the same thing as your competitors, but just a little better, is doomed to fail.

Dead in the water.

Unless you’re Amazon (or MrBeast).

Rather, being the best something for a small audience is how we niche at scale on the internet. (And Tokyo is 0.8 percent the size of the internet.)

The internet is like Tokyo, a universe of diverse needs and weird desires, an expansive opportunity space when we recognize what we’re looking at and dealing with.

Kat Norton exemplifies this truth, being the best Microsoft Excel creator to an obscure audience seeking not just an education but a transformative experience done in a uniquely fun way.

1,000 True Fans, Wired editor Kevin Kelly’s beloved essay from 2008, laid out this same theory:

To be a successful creator you don’t need millions. You don’t need millions of dollars or millions of customers, millions of clients or millions of fans. To make a living as a craftsperson, photographer, musician, designer, author, animator, app maker, entrepreneur, or inventor you need only thousands of true fans.

The number 1,000 is not absolute. Its significance is in its rough order of magnitude — three orders less than a million, reframing our perspective of what’s required for an indie creator to build a following that can support their work.

Kelly argued that the internet and digital technology have made it easier for creators to directly connect with their fans, bypassing traditional gatekeepers and building strong relationships directly with those who love what they’re doing.

As Kelly stated, not every fan will be “super.”

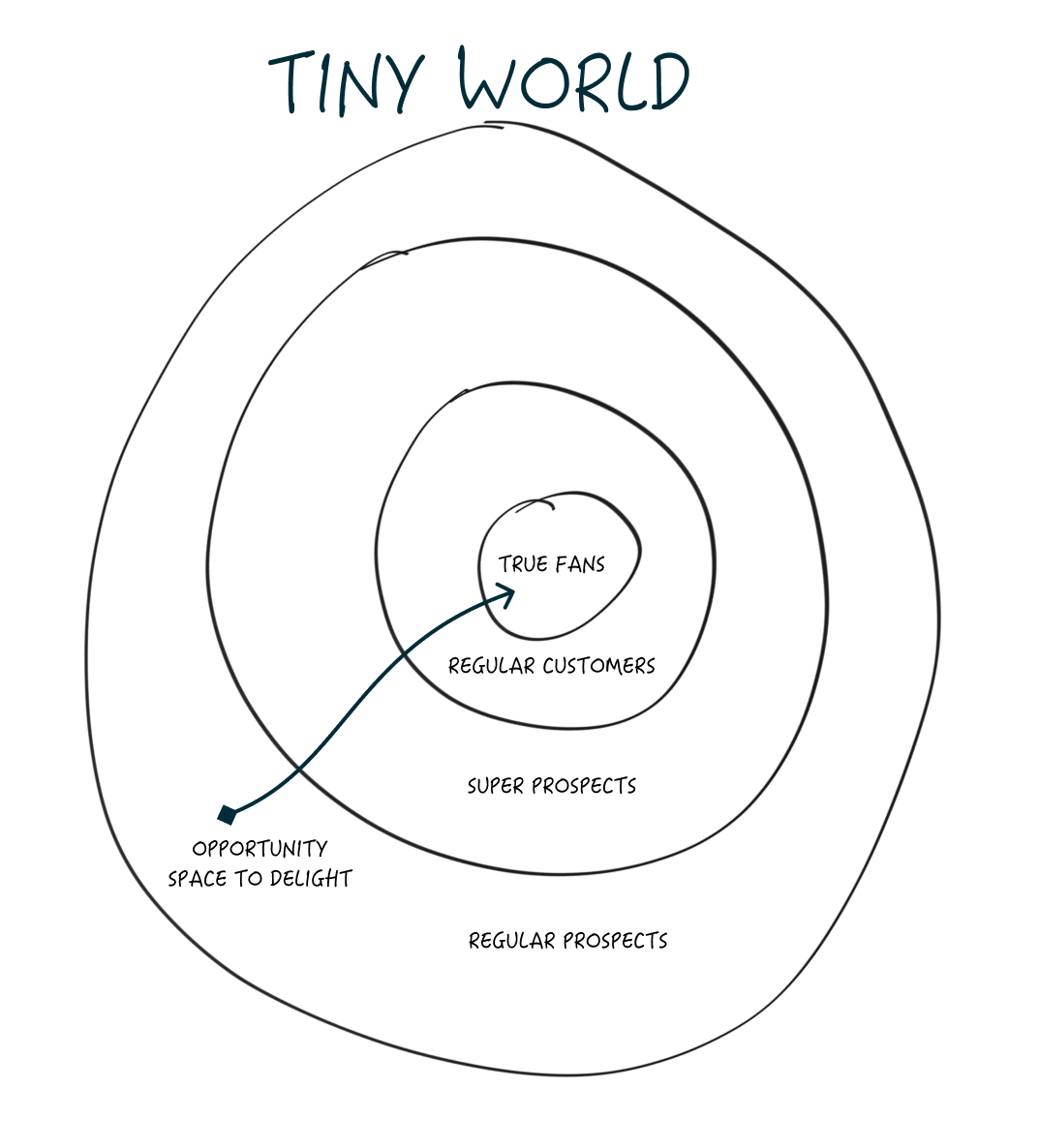

For every true fan, you might have two or three regular fans. Think of concentric circles with true fans at the center and broader circles expanding out from regular fans to super prospects, surrounded by our wider audience of regular prospects.

True fans are not only the direct source of our income but also our chief marketing force for ordinary fans and new prospects entering our world, expanding our opportunity space to delight and serve.

Delighting the Weird

Again, 1,000 isn’t an exact number. Tiny is relative.

Even earning tens of millions a year (like ConvertKit) or hundreds of millions a year (like Basecamp) can be tiny when we zoom out to see the entire city of the internet and who is being served, particularly when our mission or purpose is guided by customer-centric priorities.

In a tech-based world where founders chase VC funding and rainbow-pissing unicorns, where mass audience capture, network effects, and hockey stick year-on-year growth trump customer-funded business models, tiny is the antithesis, the enemy of scale.

But mass is not our game. We are sovereign creators playing an entirely different game.

“In life the challenge is not so much to figure out how best to play the game; the challenge is to figure out what game you’re playing.”

Kwame Anthony Appiah (via Graham Duncan, The Playing Field)

Tiny represents a philosophy of serving first, being customer-funded from the start, and being accountable only to our customers.

Tiny is about transcending the commodity-driven world of economic incentives and instant gratification.

Rather than trying to appeal to the masses, tiny emphasizes the importance of cultivating strong connections and building lasting relationships with a dedicated group of like-minded fans coming together around shared interests that matter.

Being intentionally tiny enables us to develop products and services specifically tailored to audiences with diverse needs, providing a level of attention and care (and fun) that larger companies cannot offer or compete with.

It simply means becoming invaluable to a small group of true fans and delighting them (over and over!).

“We’ve been profitable 68 straight quarters, 17 straight years. We’ve kept our company intentionally small — we believe small is a key to calm.”

Jason Fried, founder of Basecamp (source)

Recognizing the internet is like Tokyo, being tiny, and delighting the weird, is the business model for sovereign creators right fucking now (and into the post-AI world that is our future).

Delighting is a super power.

Being tiny grants us the strategic advantage of agility, allowing for quick pivots in response to changing circumstances and customer feedback.

As Jeff Bezos wrote in a 1999 letter when Amazon was still a baby, “We listen to customers, invent on their behalf, personalize the story for each of them, and earn their trust.” (Italics mine.)

Being Tiny allows us to put caring and mattering and our customers’ story at the center of our World.

In a world where the internet has unleashed a tsunami of disruption, embracing a tiny approach is the more durable way to survive and thrive.

I know it has been for me.

Over the past fifteen years, I’ve been experimenting with an expression of Kelly’s 1,000 True Fans concept, emphasizing Tiny in attracting an audience, not through coercion, but by building a “World” my audience resonated with and wanted to inhabit.